Addressing Patient Bias in Health Care

The prevalence of implicit bias in Western Medicine has become normalized in the American health care system. Smith (2019) posits “that racism exists in health care settings should surprise no one—it exists in all domains of contemporary life. What is surprising is just how little racism is formally addressed in medicine.” While there is a clear need to address the racism and bias that impact the care received by patients, there has been an increase in conversations within health care and human services organizations about how to respond to patient-on-provider bias. In addition to bias, many organizations are adopting the language “racism, discrimination, and microaggressions” or RDM, to describe these behaviors more inclusively.

We recognize that medical professionals and clinicians are often required to address issues of race and ethnicity related to health disparities within the context of delivering care. However, they are rarely given tools or resources on how to respond when they are the target rather than the patient.

To confidently identify and respond to instances of patient bias, health care professionals and clinicians first need to be able to recognize that acts of bias or discrimination are rooted in a set of multiple factors. These factors could include a complex interplay of one’s experiences of discrimination, lack of cultural sensitivity, language barriers, and many other social determinants of health. It is generally understood that when a physician and patient are of different cultural backgrounds, miscommunication due to language barriers, cultural misunderstandings, and stereotyping may present obstacles to equitable care. This cultural mismatching can understandably cause some tensions at best, but at worst, it can result in interactions that are harmful and demoralizing for providers. While these experiences are well documented by providers of color, the experience of LGBTQ+ providers who are the targets of bias and RDM is similar to the rates of racially or ethnically diverse providers.

So, What Can We Do?

Solutions to combat and disrupt the bias and RDM experienced by providers in clinical settings most certainly require a multi-pronged approach. To better equip health care professionals, providers, and clinicians with the tools and resources to respond to instances of bias and RDM competently and respectfully, a systems-level approach is necessary. Historically, the health care field has addressed issues related to RDM through cultural competency training, with lessons focused on teaching cultural practices that often impact patients’ behavior, health, or interactions with physicians. What is needed is both effective cultural competency training that addresses the complexities of cross-cultural interactions and – very importantly – policies and procedures to address instances of RDM experienced by providers.

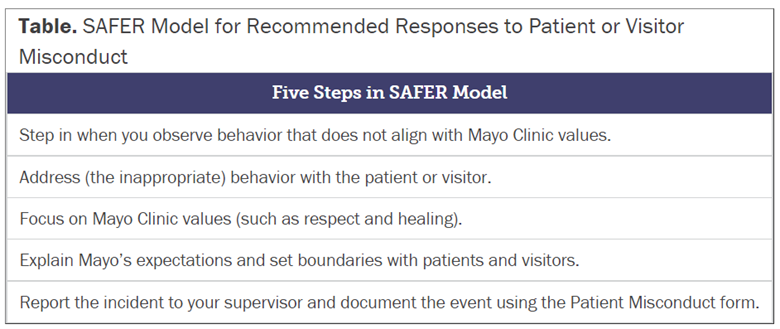

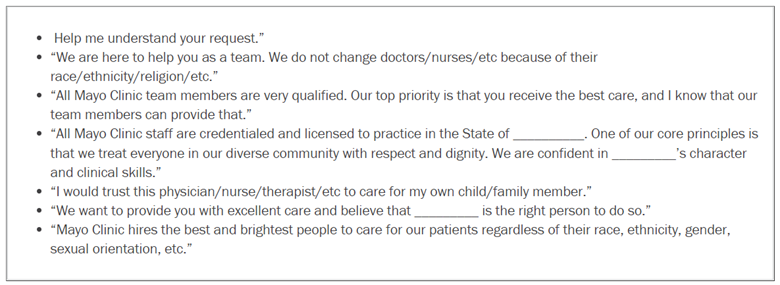

A number of health care organizations have recently developed frameworks and models to help providers address instances of patient bias and RDM. As an example, The Mayo Clinic developed a 5-Step policy (SAFER Model) for responding to bias incidents, and a corresponding script for practical use (shown below). Penn State Medical System also adopted a comprehensive Patient Rights and Responsibilities policy, which include behaviors categorized as RDM. As more organizations adopt similar policies and training for staff and providers, we hope that organizations can positively impact the experience of their providers and clinicians, confidently respond to instances of patient bias and RDM, and provide more resources for their employees’ mental, emotional, and psychological safety.

Adopting steps to address the bias, racism, discrimination and microaggressions faced by providers, such as the ones developed by the Mayo Clinic shown below, can serve as an initial framework for organizations to begin developing comprehensive policies and procedures for responding to patient-on-provider bias and RDM. While both periodic training and having a set of steps to serve as guidelines on how to respond to bias or RDM by patients are key elements, they need to be accompanied by a concerted, ongoing organizational commitment to address racism, power, and privilege at both the interpersonal and institutional levels to really have a meaningful and systemic impact.

Source: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/mayo-clinics-5-step-policy-responding-bias-incidents/2019-06

Chandler Lewis

Equity and Inclusion Program Director

The Cross Cultural Health Care Program